This story is part of Cooperation Canada’s Triple Nexus Spotlight Series

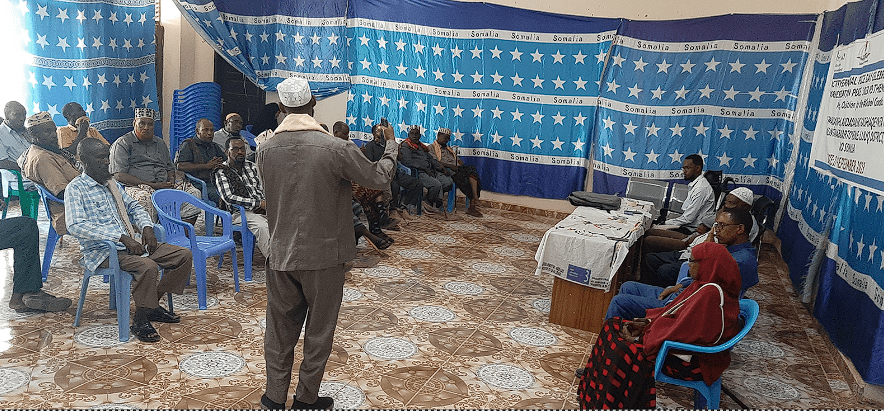

In 2020 Development and Peace – Caritas Canada, in partnership with Trócaire, initiated a three-year project to support vulnerable communities, particularly women, in Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) camps and host communities. The project, titled ‘Improving Food Security for Vulnerable IDP and Host Communities,’ aimed to establish sustainable food systems through agroecology. It focused on empowering women by equipping them with farm input, including access to land, and promoting resilient alternative livelihood opportunities, as well as community-based natural resource management. Over 2,118 (1,066 females and 1,052 males) from Luuq District in Gedo Region of Southern Somalia were reached through the intervention.

Project beneficiary harvesting on a farm provided to her to farm. Photo: CeRID

Fadhumo a 32-year-old mother of eight children, was provided with agricultural training based on sustainable farming practices, seeds, farming tools and a piece of land to grow crops. On average, Fadumo earned an income of USD 300 after every harvest that allowed her to pay USD 16 per month in school fees for her four sons who attend a local madrasa, and look after 14 members of her extended family. She saved enough money to access a loan and opened a shop. The saving groups also improved women’s confidence, engagement in decision making, and the building of a social network that they can rely upon.

Somalia, a fragile nation, has endured prolonged conflicts, climatic challenges like droughts and floods, food insecurity, inter-clan conflicts, and limited access to essential services. By mid-2023, over 1.4 million Somalis had been internally displaced due to these factors, with more than 8.25 million people urgently needing humanitarian aid. Furthermore, over 3.7 million people in Somalia are currently experiencing high acute food insecurity.

A-three-day old group of the newly IDP at the Kahare camp; they had hopes of receiving humanitarian assistance. Photo: Trócaire

This number is expected to rise to 4.3 million people between October and December 2023, including 1.5 million malnourished children, with 330,630 of them being severely malnourished from August 2023 to July. Insecurity and inter-clan clashes disrupt peace, economic development, access to basic services, and psychosocial well-being. This disproportionately affects women, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, and minority groups. The lack of livelihood resources has compromised household food consumption, compelling these populations to relocate from their homes to internally displaced persons (IDP) camps over 20 km away, seeking basic needs and services.

“The loud sounds of gunfire were deeply traumatic; some of our neighbours lost family members. Our land was taken away. We were overwhelmed by fear and left with no means of survival. So, we gathered whatever we could and left our home of over 10 years to Dollow. After a twelve-day journey on a donkey cart, non-stop, we arrived safely. Upon our arrival, we were warmly welcomed by the camp leaders, who provided us with shelter,” recounted Hawa.

Hawa and her family are among the many people who had to relocate to Gedo in search of a better and more secure life after their livelihoods were disrupted by an inter-group conflict. In this context, the triple nexus approach is crucial to tackling systemic inequalities. This approach not only connects short-term relief to lasting social progress but also fosters peaceful environments, enabling the full realization of human rights.

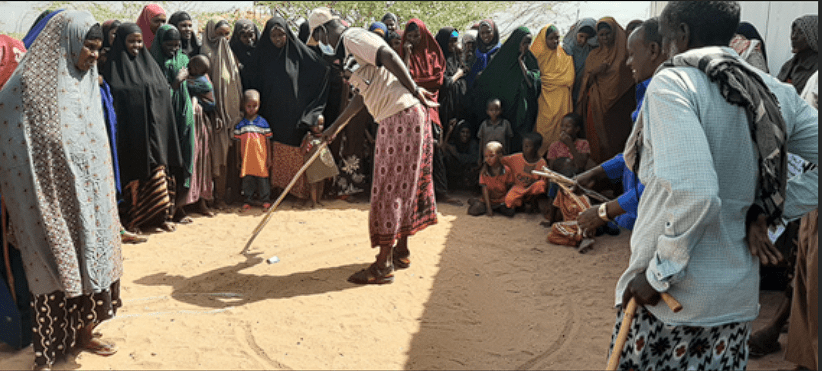

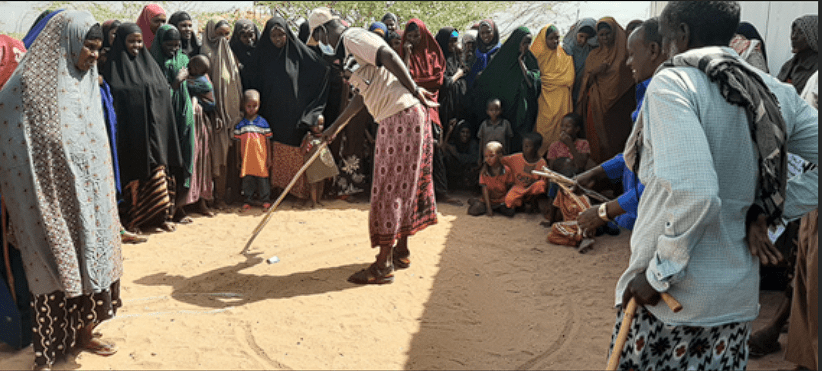

A community member from Boyle community participating in the DRR mapping exercise in Luuq District. Photo: CeRID

Trócaire uses a conflict-sensitive approach that engages with communities for feedback and information sharing around local interventions. Its programmes are integrated not only from a thematic point of view, but also jointly targets both host communities and IDPs to promote social cohesion. Trócaire works alongside communities to establish committees that play critical roles in conflict resolution. For instance, within the resilience programme, farmers established committees to aid in managing the farm and resolving farm conflicts. Collectively, they’ve set farm rules and plans, for example, through the establishment of watering schedules for each group as well as penalties for those who don’t respect these guidelines. This has promoted clear expectations for each farmer, equitable sharing of resources, and smooth running of the shared farm. In parallel, Water Management Committees (WMC), Community Education Committees (CEC), and Village Health Committees (VHCs) have played an active role in addressing resource-based conflicts. For example, locally led and formed WMC oversees the management of scarce water resources by ensuring local water systems are functional and promoting sustainable and fair access to water. These committees have coexisted and supported each other, where the WMC’s management of water resources has been supported by the CEC’s efforts to engage with both local and IDP communities to raise funds for school development.

Trócaire has supported the formation of other community-based committees (named, ‘community peace champions’), including Natural Resource Management and Disaster Risk Reduction committees. These work on promoting peaceful coexistence among their communities, disaster risk reduction and natural resource management to protect the environment, sustainable exploitation of resources and reduction of climate related shocks and conflict. The committee members are comprised of people from different socioeconomic strata of the community who have received training. In turn, these individuals represent the voices of the community they serve, identifying priorities through consultations that are partly supported by Trócaire.

These committees collaborate closely with community members, institutions, and local leaders that fully recognize and acknowledge their presence and work in fostering peaceful coexistence. They work within their respective communities and are the first point of contact when conflicts arise. For example, at the negotiation stage between the conflicting parties, a delegation of community elders and local leaders is convened.

The elders have not only recognized but also commended efforts made to promote peace. Following a sensitization session, community leaders expressed their sentiments, emphasizing the paramount importance of peace.

“Without peace, nothing can be achieved, blacksmiths cannot forge metals, people dare not light fire for fear of attack, access to water sources becomes impossible and life itself becomes unstable,” one leader remarked.

Another leader added, “In times of violence, no son is born, but instead we lose many young and productive men.”

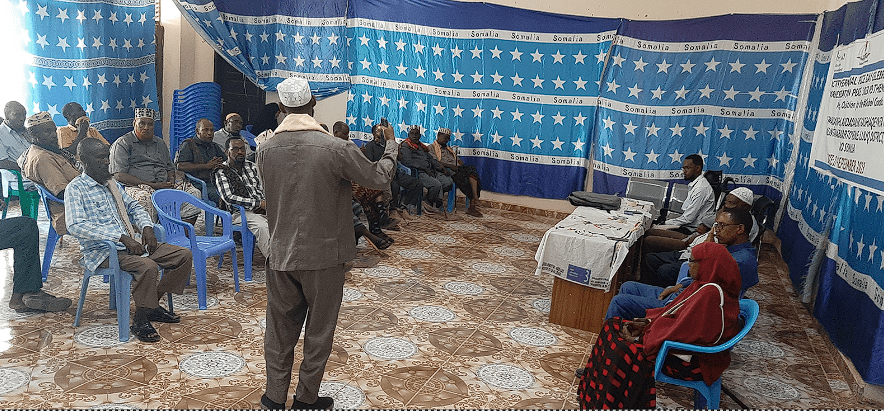

A peace building session in Gedo; aimed to sensitize community leaders on the importance of fostering peace. Photo: Mohamed, Trócaire

Trócaire recognizes that gains made through community-level peacebuilding are only sustainable if these are hinged upon community ownership. As such, collaboration and coordination with local institutions, District Health Boards, IDP leaders, local authorities, and government officials are central to the design of Trócaire’s action and programmes. These collaborations not only ensure conflict management in communities, but also provide a conducive environment for the implementation of the Humanitarian Development Plan (HDP) and ensure communities, both host and IDPs, can enjoy a broad range of rights.

This piece was co-written by Maurine Akinyi, Programme Support Officer, Trócaire Somalia and Dominique Godbout, Humanitarian Program Officer, Development and Peace-Caritas Canada.